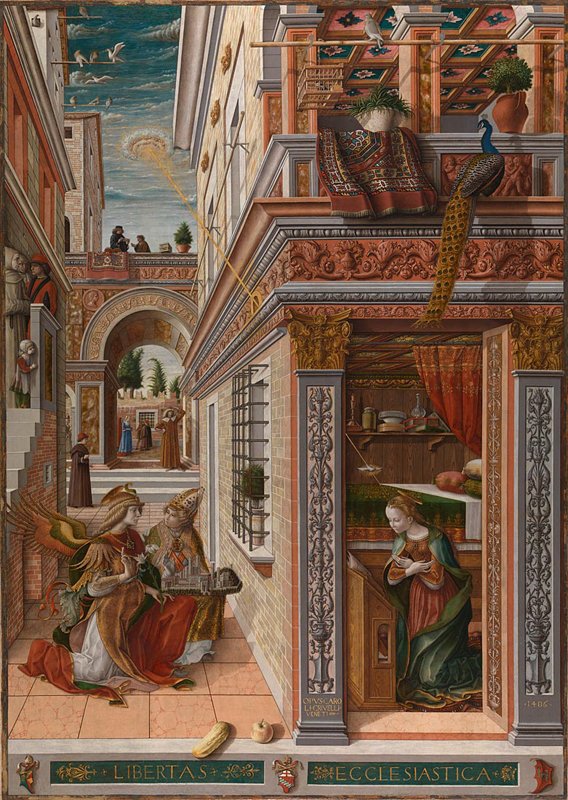

The Annunciation With St Emidius, carlo Crivelli

The Annunciation with St Emidius, Carlo Crivelli, 1482. Single panel, tempera and oil on poplar.

Wondering around the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery, it is clear the collection has been assembled in a loose stylistic/chronological order, which in turn dictates how a guided tour of the gallery may be arranged. Inevitably such a tour will include the van Eicks, Leonardos and Raphaels and presumably such an overview would regimentally define the stylistic difference between any these subjects.

Yet, some artists can’t be easily pigeonholed to one particular style and rightly so. One such old master, is the Venetian Carlo Crivelli, whose Annunciation with St Emidius, without fault always attracts the attention of the casual visitor. This large Pala, is not the only Crivelli work on display. The NG, in fact holds the second largest collection of Crivelli’s in the world, after Milan’s Pinacoteca di Brera. Many of these works are actually fragments of dismantled polyptychs and altarpieces, dispersed in the C19, when there was a race to get hold of any Renaissance work by any Italian artist.

Demidoff Polyptych, 1476

It was the Pre-Raphaelites here in Britain, who enthusiastically rediscovered Crivelli, mid C18 and this led the young American art critic Bernard Berenson, to champion him, making him a household name in the US. At the turn of the century a Crivelli was as valuable as a Botticelli at auction. However, interest in the Venetian artist waned in the mid C20, when the modernist outlook of the time disparaged the ornamental excesses of such works, Berenson distancing himself from what he described as a ‘youthful infatuation’.

But, perhaps what has hindered Crivelli’s fame the most since the C16, has been his exclusion from Giorgio Vasari’s The Lives, which coloured the views of art historians for centuries to come in the appreciation of Renaissance art. It is not quite clear why he was not included, as Crivelli was the most prestigious painter in the region known as the Marches of Ancona, where he was knighted. It is most likely that the Venetian’s stylistic ambiguity did not fit, Vasari’s Florentine-centric agenda.

One of the largest Crivelli works in the NG is the Demidoff Polyptych, a re-assemblage of the S. Domenico Altarpiece. Despite some anatomical, perspectival and trompe l’oeil techniques which we recognise as Renaissance-like, it screams International Gothic. This can be appreciated in the architectural gothic frame which encases each figure, the gilded heavenly background, the patterned halos, the 3D high relief details of St Peter’s vestments and actual wooden keys he holds which project from the canvas.

Madonna della Rondine or Virgin of the Swallow, 1490-92

Just a few yards away you will find the equally sumptuous Madonna della Rondine, which shows the Virgin with Child, flanked by St Jerome and a non-pierced St Sebastian. More akin to a Renaissance Sacra Conversazione, nonetheless every surface is highly decorated and is reminiscent of Netherlandish painting.

A look at the altarpiece’s predella, will alert the viewer of Crivelli’s narrative abilities, with a variety of conventional depictions which shows his interest in anatomy, perspective and modelling of human forms and light, although I must admit his knotty musculatures and elongated fingers are an acquired taste.

To prove Crivelli’s Renaissance credential however, we have to go back to his Annunciation, and appreciate its dramatic single point perspective, the life-like and expressive characters and the classical architecture of a Renaissance city.

Commissioned by the order of Observant Franciscans in the town of Ascoli Piceno, it was unveiled on the feast of the Annunciation of the Virgin, the 25th March 1482. It depicts the moment the Archangel Gabriel announces to the Virgin Mary, she will bear the son of God, but unconventionally a third figure is present: St Emidius, patron saint of Ascoli. In his lap is a model of the city and it is pretty obvious he is asking Gabriel to put in a good word on behalf of the town.

Madonna della Rondine predella. From left to right: St Catherine, St Jerome in the desert, the Nativity, the Martyrdom of St Sebastian, St George Slaying the Dragon

Crivelli has cleverly doubled the function of the altarpiece by both fulfilling its religious programme and adding a civic element to it. For the work was also meant to celebrate the recent confirmation of the city’s semi-autonomous status, granted by a papal bull and emphatically displayed on the plinth in the foreground: Libertas Ecclesiastica. The sacred Biblical episode is mirrored by the councillor reading a note delivered by the caged pigeon on the bridge, beneath the vortex of angel’s from which the heavenly ray shoots towards the Virgin.

Once the narrative is established, the work becomes a feast to the eye, with the elaborate grotesques decorating the pilasters flanking the Virgin’s bedroom entrance; conspicuous consumption items of a wealthy city seen in the two Anatolian carpets; the medallion above the bridge’s arch, a symbol of Ascoli’s Roman foundation, and other fascinating details and figures.

Plinth displaying Libertas Ecclesiastica and the gourd in trompe l’oeil technique

Furthermore, by comparing these various works, it becomes clear that Crivelli implemented different stylistic approaches to fulfil the tastes and demands of his Marchigian patrons, and that he was not unaware of the innovations taking place in Tuscany, but on the contrary implemented these in accord to the brief.

One more Crivelleschi element to be noted, is the trompe l’oeil gourd projecting over the plinth in the foreground. This is generally thought to be a sort of signature, his own ex-voto or devotional offering to the Virgin. It is likely he became enthusiastic with the vegetable and fruits (ever present in his works), along with other members of the Squarcione circle in Padua, where it is believed he studied with Andrea Mantegna and Cosme Tura amongst others, under the tutelage of Francesco Squarcione, learning perspectival theory and classicism.

This devotional interaction with his own works may suggest one more important element to the Crivelli puzzle. The plinth on which the gourd rests, acts as tangible surface which links our earthly world to the heavenly scene. Crivelli was obsessed with ornamenting his works with so much detail in an effort to give us a glimpse of the glory of Heaven, its beauty, riches and spiritual depth. It is no coincidence that some argue Carlo Crivelli is the first Surrealist painter!